Whom Shall We Serve?

Whom Shall We Serve?

Bob Stillerman

A Sermon for Sardis Baptist Church

Joshua 1:1-9

8-19-2018

Whom Shall We Serve Joshua 1.1-9 8-19-2018

Joshua and the Israelites stood poised to move east toward the Land God promised. And all my life, in story and song, I’ve heard about this promised land, one flowing with milk and honey. But I’ve never been able to visualize its richness. Fleming James describes this area, a little bigger than New Jersey, and a little smaller than Connecticut, in splendid fashion. His description is a little long, but I think it’s helpful for an understanding of today’s lection. James writes:

The high plateau of Moab, running northward into Gilead, rose 200 feet above sea level and descended into the Jordan Valley, which at its lowest point drops 1290 feet below the Mediterranean. Westward, they saw the great backbone of the central range, extending southwards and northwards as far as the eye could reach, rising a sheer three quarters of a mile into cooler air, attaining an elevation between 2000 and 3000 feet above the ocean. Westward, out of their sight, it dropped more gently with its tangled valleys to the lower hill country, then down to the coastal plain and the limitless Mediterranean beyond. Down the Jordan Valley, with its disorderly deposits of white marl, the river ran amid a jungle of green to the Dead Sea, whose sapphire waters disappeared southward into a haze of heat-moisture. Northward up the endless valley between parallel mountain walls they could see the white snow of Hermon lying low on the horizon. It was a land in which one could pass in a few hours from the palms of Jericho to the oaks and terebinths of the central range, then down again to the citrus groves of the coastal plain. To their eyes, accustomed to the barren wastes of the desert, it must have seemed a land of marvelous fertility, watered as it was by rains in autumn, winter, and spring, and summer drenched with nightly dews deposited by the damp wind from the Mediterranean when it struck the cooler hills. It had many springs and a few unfailing streams. The stony hillsides were terraced with vineyards or ranged over by flocks of black goats and white sheep. Olive and fig trees abounded, and pomegranates also were found. Wheat was raised in level spaces. Northward were fertile valleys rich in grain. Much of the year, the sky was generally cloudless, and the hills with their many-coloured rocks stood out brilliant in the sunshine.[1]

To quote Tina Fey, “I want to go to there!!!” The land of Canaan was an ideal spot for settlement.

And today, God says to Joshua and his people, “You get to cross over into this place. And everywhere the soles of your feet touch, plains, mountains, river banks, fields, all of it, it’s yours!!!

God continues: “But that’s not all. No one shall oppose you – I’ve made it so that it’s yours, as long as you live. You and me, we’re bound in this covenant together. Be strong, and courageous, for I am with you, wherever you may go.”

And I wish, oh how I wish, the story ended here. Because if it ends here, we simply assume that God has rewarded an enslaved, wandering people with a beautiful, productive slice of uninhabited land. This, this is the stuff of the Jubilee – a people living in shared abundance, all connected together by God, land, and neighbor. A covenant people living into all of God’s possibilities.

But unfortunately, the story doesn’t end here. What happens next are twenty-four chapters of conquest. The Israelites seize the lands from the Canaanites over the course of successive battles. Ordained by God’s blessing, and buoyed by God’s sword, Joshua and the Israelite systematically eliminate the Canaanites from their lands. And the crime of the Canaanites is not that they were aggressors or conquerors, but rather, they were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

And especially troubling in the stories of Joshua is the practice of herem, which is the total annihilation of the enemy – its people, its buildings, its livestock, anything that can be considered a spoil of war – all of it destroyed as a sacrifice to YHWH.

The God that Joshua describes is a Warrior God. And the God of Joshua takes sides. And the God of Joshua owns a covenant crippled by a shallow sense of mercy and a limited sense of creativity.

And I think our initial reaction to all of this is: What do we do with stories like these? Because it’s hard to reconcile a God of love, who also has a taste for blood and violence.

So let’s try a couple of things.

One, Fleming James laments that Joshua’s story is so intertwined with a War-God. There are pieces of this God in Exodus, too, but balanced with the fairness and compassion of the Mosaic tradition. James believes that Joshua is left to shoulder the majority of the regrettable details/nastiness of settling a new land. And he thinks that over the years, tradition so over-emphasized the stories of conquest, that it de-emphasized the qualities of Joshua that made his faith SO steadfast in YHWH. Surely Joshua treasured a sense of compassion and fidelity made known in YHWH’s covenant. And his zeal for YHWH, though misplaced in militance, was sincere.[2]

Two, Joshua is considered to be a writing of Deuteronomic history. In all likelihood, it was redacted into its final form by writers in the era of King Josiah, who instituted many reforms to the Temple Cult. John J. Collins notes that the Kingdom of Judah was still reeling from the shock of seeing its northern neighbor Israel eviscerated by the Assyrians. Josiah worked hard to create a strong national identity. The language of these stories is a tool of national propaganda.[3]

Three, to date, modern archeology has yet to reveal significant evidence, and even minimal evidence, of either a mass exodus from Egypt into Canaan, or a military conquest and genocide of its major fortifications that would have occurred in the time periods described in Exodus and Joshua.

So….these stories are most likely high on hyperbole and short on historical details. And they are not to be considered absolute statements made by God for God’s people, but rather reflections of how Israelites saw and understood their God. It’s the earliest form of the prosperity gospel: God’s love and fidelity are not born out simply in our existence as children of God. But rather, God’s love and fidelity are made known in tangible things: territories, riches, power, victories, etc.

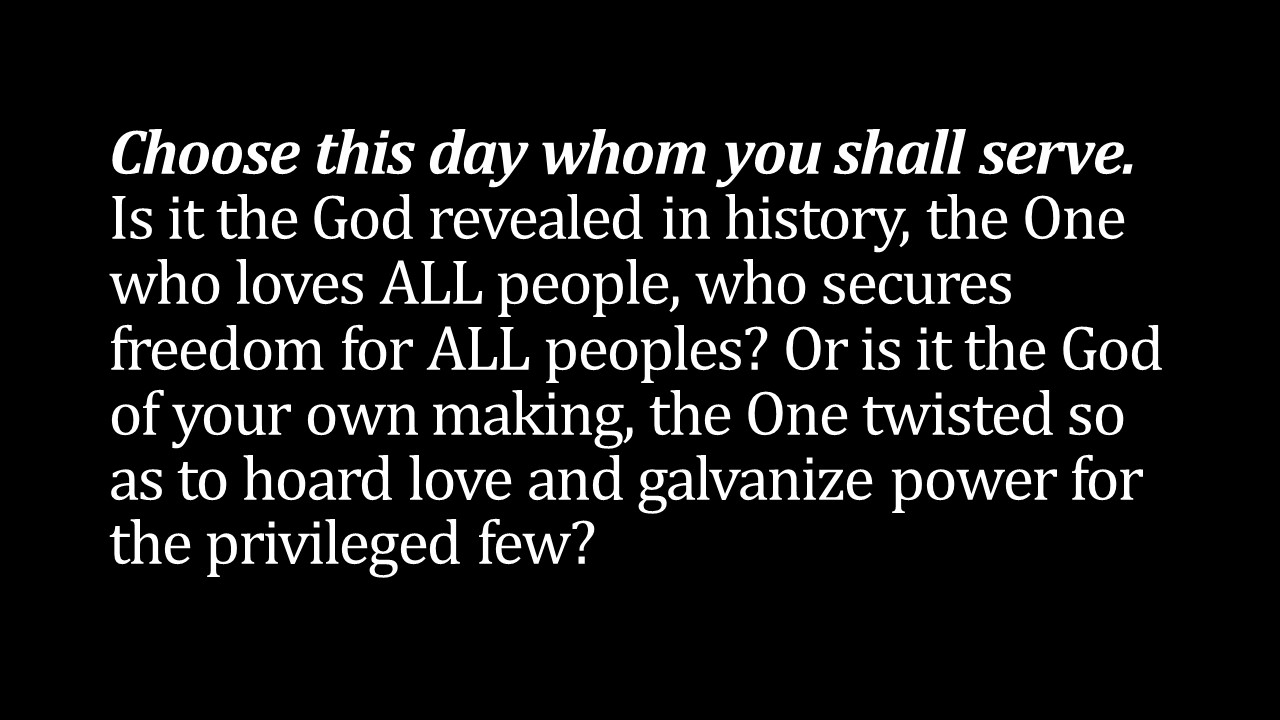

And though it’s not in today’s lection, Joshua ends with a rather famous quote. Having settled the land, Joshua says to his people: “Choose this day whom you will serve. As for me and my house, we shall serve the Lord.”

And, I’ll admit it. I want to be like Joshua. I want to serve God. And I want to experience a new land flowing with milk and honey. But I don’t want to be like the Joshua twisted by tradition, and mimicked through the centuries in acts of colonization and assimilation.

I want to ask, “Who is this God I choose to serve?” Is it the God of creation, the one revealed in acts of love and kindness and mercy? Or is it the God I choose to create for myself, the one who asserts my privilege, and my interests, and my welfare at the expense of my neighbors?

I guess what I’m saying, Sardis Baptist Church, is what kind of God do we want to serve, and what kind of Canaan do we want to help create?

When we drive through poorer neighborhoods in Charlotte, what do we see? Do we see plots of land teeming with potential, ready to have new life breathed into their residents: jobs for adults, schools for children, happy songs to sing and diverse gifts to share, a spirit to rekindle old fires. A spirit of inclusion that says prosperity is not a zero-sum proposition. Or do we see an opportunity to take what should have belonged to us already – a chance to re-gentrify; a chance to build new luxury high rises; a chance to villainize those Canaanites for living in the paths of our progress?

When we think about the global Church, what do we see? Do we see hundreds of millions of diverse, gifted, loving, serving souls, all sitting at an ever-expanding table? All working to bring about God’s kingdom moment by moment? Or do we see something that needs to fit a rigid mold? Is it time to spell out what real theology is? Is it time for clergy and lay leaders to twist God, and use our power such that we abuse, both openly and privately, the marginalized who long for God’s acceptance? Is it time we take back the Church for the real people of God, and leave those Canaanites to fend for what’s left?

Citizenship. Employment. Housing. Food. Security. Love. Belonging. Is there a land big enough that such things can be available to both Israelite and Canaanite alike?

Choose this day whom you will serve. I choose to serve the God of Joshua. Not the one tradition molded for him. But the One revealed to him. The same One revealed to Moses on Holy Ground, and to Hagar in her hour of deepest need, and to Hannah in her song, and to Mary in her faithfulness, and to Jesus in the breaking of bread.

And I choose to work for the Canaan God calls us to make, the described by the prophet Joel:

God’s spirit will be shed on all humankind, sons and daughters shall prophesy, old men will dream dreams, and young men will see visions, and everyone who calls on God’s name will be saved. Even the Canaanites. Especially the Canaanites.

May it be so. And may it be soon. Amen.

[1] Fleming James, Personalities of the Old Testament (Charles Scribner and Sons: New York, 1949), 48-9.

[2] Fleming James, Personalities of the Old Testament (Charles Scribner and Sons: New York, 1949), 56-7.

[3] John J. Collins, Introduction to the Hebrew Bible (Fortress: Minneapolis, 2004), 185-7.

Recent Sermons

Jesus’ Final Word

May 18, 2025

Resurrection as the Long Game

May 11, 2025

Christ Honors Our Bodies

May 04, 2025